Old coins often have dirt, corrosion, oil, or other “gunk” on them. It can be tempting to clean them with powerful industrial cleaners, silver polish, Shine Brite, or other chemical cleaners.

However, this is a bad idea.

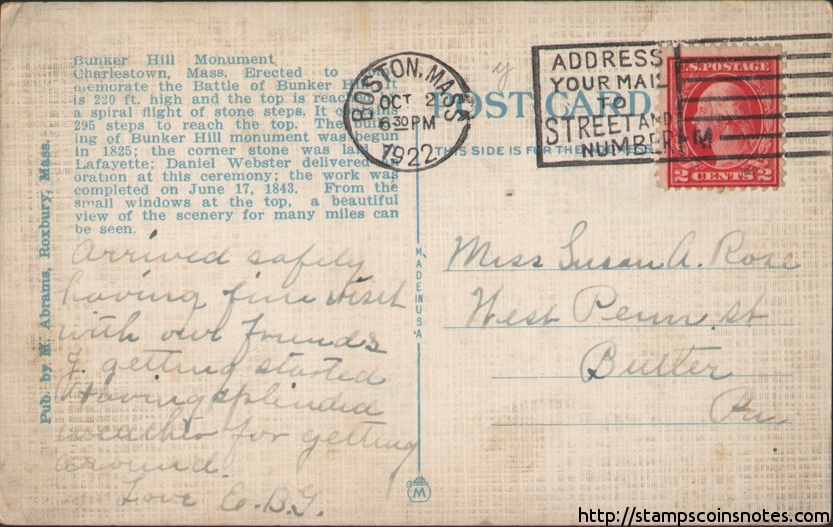

Over time, coins develop oxidation, discoloration, and a layer of grime. This is called a patina, or more commonly in numismatics, toning.

Natural Toning on a Mercury Dime.

Chemical cleaning agents will remove toning. A coin in its natural toned state is more valuable, so removing toning will reduce a coin’s value and collectibility. An ugly old coin may not look as appealing to most people, but a shiny, artificially new-looking coin from the 1920s with a noticeably worn face is unappealing to an experienced collector.

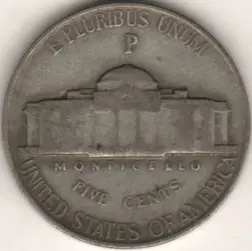

It is possible to add false toning to a chemically cleaned coin with something like Midas Black Max Oxidizer, which uses hydrochloric acid and tellurium to create an artificial patina. This is technically a form of counterfeiting and is not recommended, as it renders a coin numismatically worthless. It may be a fine choice when recovering corroded old coins to turn into jewelry, but that is the only sane use for such a thing.

Cleaned and False-Toned Mercury Dimes for Use in Jewelry Manufacture. Image Courtesy of Dean Moore Designs.

The only safe way to clean a coin is with a gentle wash in mild dish soap and water. If that can’t remove the excess grime from your coin, then it wasn’t meant to be removed.

Coins should be washed by hand in a plastic container, because rubbing them against a metal sink can scratch them, as can some cleaning pads and brushes. Using steel wool to clean coins would be an especially bad idea. Rub the coin with your fingers from the center outward to push dirt, oil, and grime toward the edge of the coin.

After washing, rinse the coins with clean water to remove all remaining soap residue. Distilled water is preferred.

You should pat coins dry with a soft towel after rinsing and make sure they are completely dry before storing them. After rinsing, you should only handle coins by the edges to avoid adding more oil from your hands.

Be careful of residual moisture when cleaning coins. Some 20th-century coins from Romania and the Soviet Union are prone to rust if kept wet for any length of time. Their plating is not sufficient protection for the ferrous core of those coins. Soaking them is not a good idea. Other coins can be safely soaked for a bit to loosen grime. For example, an old piece of candy cane clinging to a coin isn’t just going to wash off. It’ll need to soak for a few minutes.